March 2020.

In these days of forced isolation, in which nobody is truly safe, yesterday’s vulnerable ones are even more so, and more alone. If my mother and father were alive, I would be far from them. The geographical distance that descends from a life choice is very different from an imposed distance, one in which the parent dies alone, the last breath inside a respiratory helmet; their body sprayed with disinfectant and wrapped by a stranger in a sheet; transferred, without further care, to the morgue; and finally, cremated in their own or an alien city, far from the family’s tears. My thoughts go to the Foscolian sepulchres, to the void that replaces the stone on which to mourn a lost loved one, to the exiles inside and outside the homeland (away from the land to which they felt they belonged); to the days, long gone, when I said goodbye to my parents, and the day when I combed Mum’s hair, which continued to grow after her laboured breathing had stopped.

Exile has many forms, but this is perhaps the first time that our present resembles that of those who come from the sea and still risk, in order to save their own lives, to die alone.

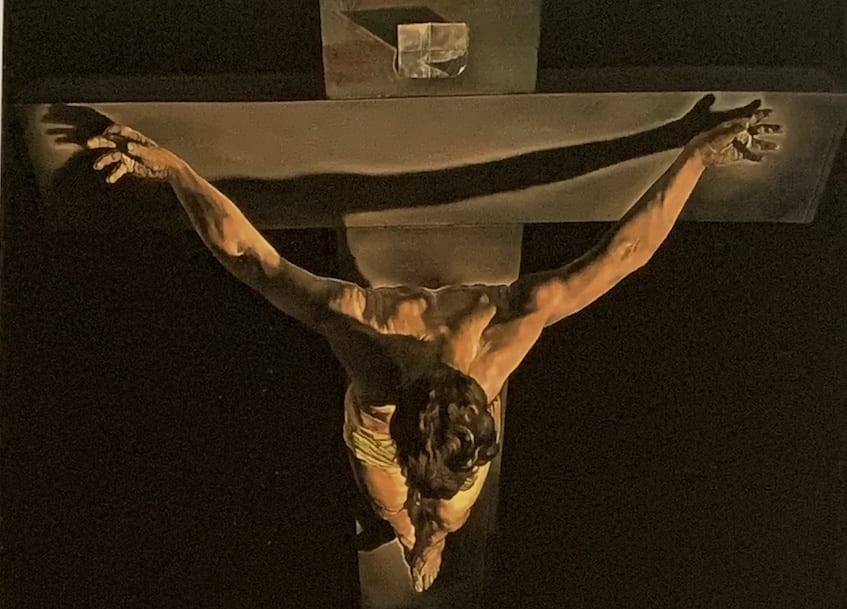

Everyone dies alone, it will be said; when we cross the door of life, nobody is with us. But like in every big step, we want to be held by the hand.

December 2015. Island of Lesvos.

It is around 7 in the morning on a December day. The first dinghy I will see arrive looks like a flower. It appears in the distance, and from the beach, I am the first to see it. But I do not announce it; you do not announce flowers on the water. When I start to see the petals, someone shouts the sighting to the other volunteers. The floating corolla grows bigger, and my eyes are fixed and hypnotized, because no photograph I have seen before looked like this. The flower approaches the shore and becomes people calling for help. And I do not know what to do; because you smile at flowers, so I do not really know if what I am feeling is wrong.

My eyes land on a woman wrapped in a blanket. Everyone is busy with someone else, so I choose her. I do not know how to behave; I am terrified of saying or doing something stupid, or wrong, or inappropriate. Everyone who got off the dinghy is wet, cold and shaking. The most urgent needs of the body allow their respective owners not to think, not yet; and this helps both: the arrivals and those who welcome them.

I lean slightly towards the woman, and I see my mother travelling alone to a remote country that speaks an unknown alphabet, after having lived in a house familiar to her, the furniture unchanged for fifty years. I remain silent; my right hand instinctively reaches her left shoulder and caresses the rough, grey blanket – perhaps only to suggest not to be afraid, perhaps in the hope that that little friction will turn into heat and reach the body under the blanket.

And the woman burst into tears. An inconsolable, unstoppable weeping. And although a year from now I will read in those tears the cry for the lost life, for the far homeland, for one’s identity seen from the shore of a remote country after surviving the surreal crossing of an arm of the sea onboard a piece inflatable rubber, tight in a crowd of strangers, at this moment I am certain that it was my clumsiness to have caused it; and maybe I said I’m sorry, and I cried too.

But I do not remember anything else.

There would be no closed doors if each of us saw this, even for once only.